Recently I completed the restoration of a really interesting piece. I was in a local antiques store called the Gilded Flea (http://www.gildedflea.com/) talking with the owner and looking at the new arrivals. As I was about to leave I noticed corner cupboard, which up to that point I had completely missed. I happened to have a customer who had been hunting for a corner cupboard. One stipulation was that the top be open for displaying purposes. I took a few photos and measurements and sent them to my customer, who bought the piece almost immediately.

A few days later I returned to the Gilded Flea with my van and transported the cupboard to my shop. Once the cupboard was in the shop I started to look it over to get an idea of what repairs needed to be addressed as well as get acquainted with the piece. Below are the original photos I took of the piece while it was displayed in the Gilded Flea.

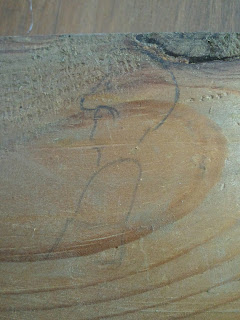

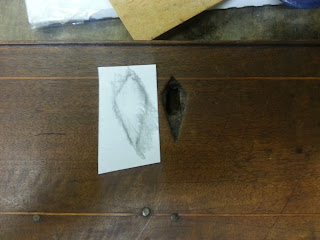

Dwayne, The co-owner of the Gilded Flea, had informed me that the piece was signed on the back. Below is a photo of the signature. The photo that follows is a doctored version to help clarify the signature. The signature reads "William Henry Dietz- Rt.1- Manchester"

The molding which framed the opening in the top was very loose, so it was glued in place, as seen in the photo below.

It is hard to see in these photos, but the interior of the base was very dirty and had many rings on the shelves. The entire interior was sanded and stained.

One of the shelves was loose and the joint had failed. Below is a photo of it being glued.

Many of the nail holes in the back and shelves were filled and sanded, in preparation for painting the interior of the top.

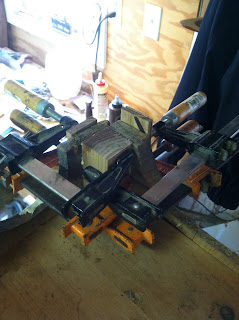

The drawer bottom was separated, but it was possible to glue the two boards that make up the bottom back together, as seen in the next two photos

The last two photos show the piece once the painting was done and the finish was restored. It really turned well and the customer loved it. Thanks to Dwayne and Krista at the Gilded Flea for the great find!

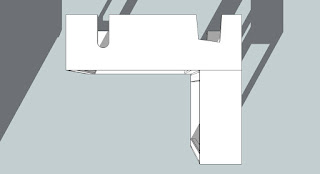

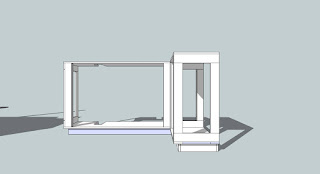

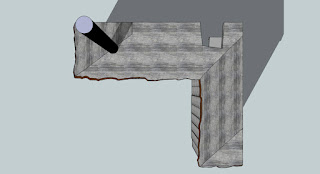

A few days later I returned to the Gilded Flea with my van and transported the cupboard to my shop. Once the cupboard was in the shop I started to look it over to get an idea of what repairs needed to be addressed as well as get acquainted with the piece. Below are the original photos I took of the piece while it was displayed in the Gilded Flea.

Dwayne, The co-owner of the Gilded Flea, had informed me that the piece was signed on the back. Below is a photo of the signature. The photo that follows is a doctored version to help clarify the signature. The signature reads "William Henry Dietz- Rt.1- Manchester"

A little digging revealed that the only instance of Route 1 going through a town named Manchester, was in Virginia. It turns out that the south side of Richmond which lies on the south bank of the James River was originally a separate town named Manchester. Manchester was annexed by Richmond in 1910. Route 1 crosses the James river over Belle Isle and passes through Manchester as it heads south. A little more digging revealed that Route 1 was laid out around 1920. While these dates do not overlap, it is easy to imagine that a cabinet maker who grew up in Manchester would have continued to call his home town Manchester even after it was annexed by its neighbor. The only thing was that the base was clearly much older than these dates. Closer inspection revealed that while the base was signed by William Henry Deitz, it was signed on replaced boards in the back. Most likely, Mr. Dietz had the base, which probably dates to around 1850, fixed and refinished it, and built the top to fit the base. The top has several design elements that place it in the twentieth century, and the nails and saw marks are consistent with this. The base is pegged and square nails were used, pointing towards earlier construction. Both top and base were made primarily of Poplar.

The final conclusion that I have come up with is that the base was made around 1850, probably in Virginia. Around 1920 or so Mr. Dietz got a hold of the base and repaired and restored it. In addition, he made a new top for it complerte with doors. The doors are currently missing, which suited my customer just fine, since she was looking for a piece without doors. Below are some photos of the piece during the restoration process.

The next two photos are of the top and base as they came into the shop.

The molding which framed the opening in the top was very loose, so it was glued in place, as seen in the photo below.

It is hard to see in these photos, but the interior of the base was very dirty and had many rings on the shelves. The entire interior was sanded and stained.

One of the shelves was loose and the joint had failed. Below is a photo of it being glued.

Many of the nail holes in the back and shelves were filled and sanded, in preparation for painting the interior of the top.

The drawer bottom was separated, but it was possible to glue the two boards that make up the bottom back together, as seen in the next two photos

The last two photos show the piece once the painting was done and the finish was restored. It really turned well and the customer loved it. Thanks to Dwayne and Krista at the Gilded Flea for the great find!